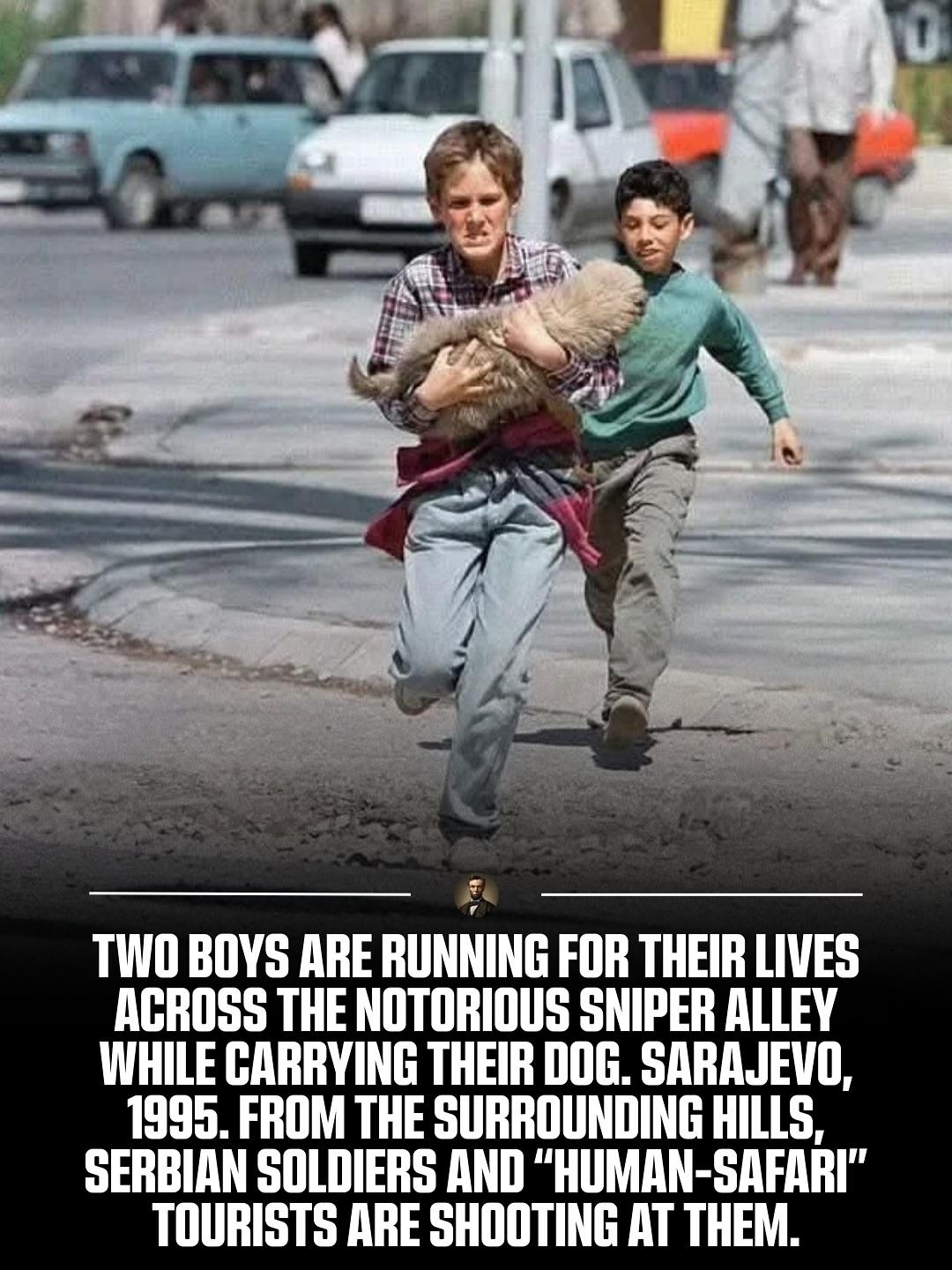

Two boys are running for their lives across the notorious Sniper Alley, clutching their dog to their chests as they sprint. Sarajevo, 1995. For nearly four years the city has been under siege, its residents trapped in a landscape where everyday errands can turn into deadly gambles. The boys know the rhythm of danger by heart—the moments of deceptive calm, the sudden crack of a rifle from the surrounding hills.

From the ridgelines that encircle the city, Serbian soldiers watch for movement through their scopes. Mixed among them are thrill-seeking foreign “human-safari” tourists who have come to witness, and sometimes participate in, the deadly sport of targeting civilians. Every dash across an exposed street is a roll of the dice.

The boys run because they must. Their dog had broken loose during a mortar blast the night before, and retrieving him meant crossing one of the most perilous stretches of open ground in the city. The animal whimpers in their arms as they sprint past the bullet-pocked facades, weaving between burned-out trams, hoping the next shot is not meant for them.

Behind them, the city groans under hunger, fear, and exhaustion. Ahead of them lies only a few dozen meters of open asphalt—but in Sarajevo during the siege, that is distance enough for life or death.

From the ridgelines that encircle the city, Serbian soldiers watch for movement through their scopes. Mixed among them are thrill-seeking foreign “human-safari” tourists who have come to witness, and sometimes participate in, the deadly sport of targeting civilians. Every dash across an exposed street is a roll of the dice.

The boys run because they must. Their dog had broken loose during a mortar blast the night before, and retrieving him meant crossing one of the most perilous stretches of open ground in the city. The animal whimpers in their arms as they sprint past the bullet-pocked facades, weaving between burned-out trams, hoping the next shot is not meant for them.

Behind them, the city groans under hunger, fear, and exhaustion. Ahead of them lies only a few dozen meters of open asphalt—but in Sarajevo during the siege, that is distance enough for life or death.

Two boys are running for their lives across the notorious Sniper Alley, clutching their dog to their chests as they sprint. Sarajevo, 1995. For nearly four years the city has been under siege, its residents trapped in a landscape where everyday errands can turn into deadly gambles. The boys know the rhythm of danger by heart—the moments of deceptive calm, the sudden crack of a rifle from the surrounding hills.

From the ridgelines that encircle the city, Serbian soldiers watch for movement through their scopes. Mixed among them are thrill-seeking foreign “human-safari” tourists who have come to witness, and sometimes participate in, the deadly sport of targeting civilians. Every dash across an exposed street is a roll of the dice.

The boys run because they must. Their dog had broken loose during a mortar blast the night before, and retrieving him meant crossing one of the most perilous stretches of open ground in the city. The animal whimpers in their arms as they sprint past the bullet-pocked facades, weaving between burned-out trams, hoping the next shot is not meant for them.

Behind them, the city groans under hunger, fear, and exhaustion. Ahead of them lies only a few dozen meters of open asphalt—but in Sarajevo during the siege, that is distance enough for life or death.

·136 مشاهدة

·0 معاينة