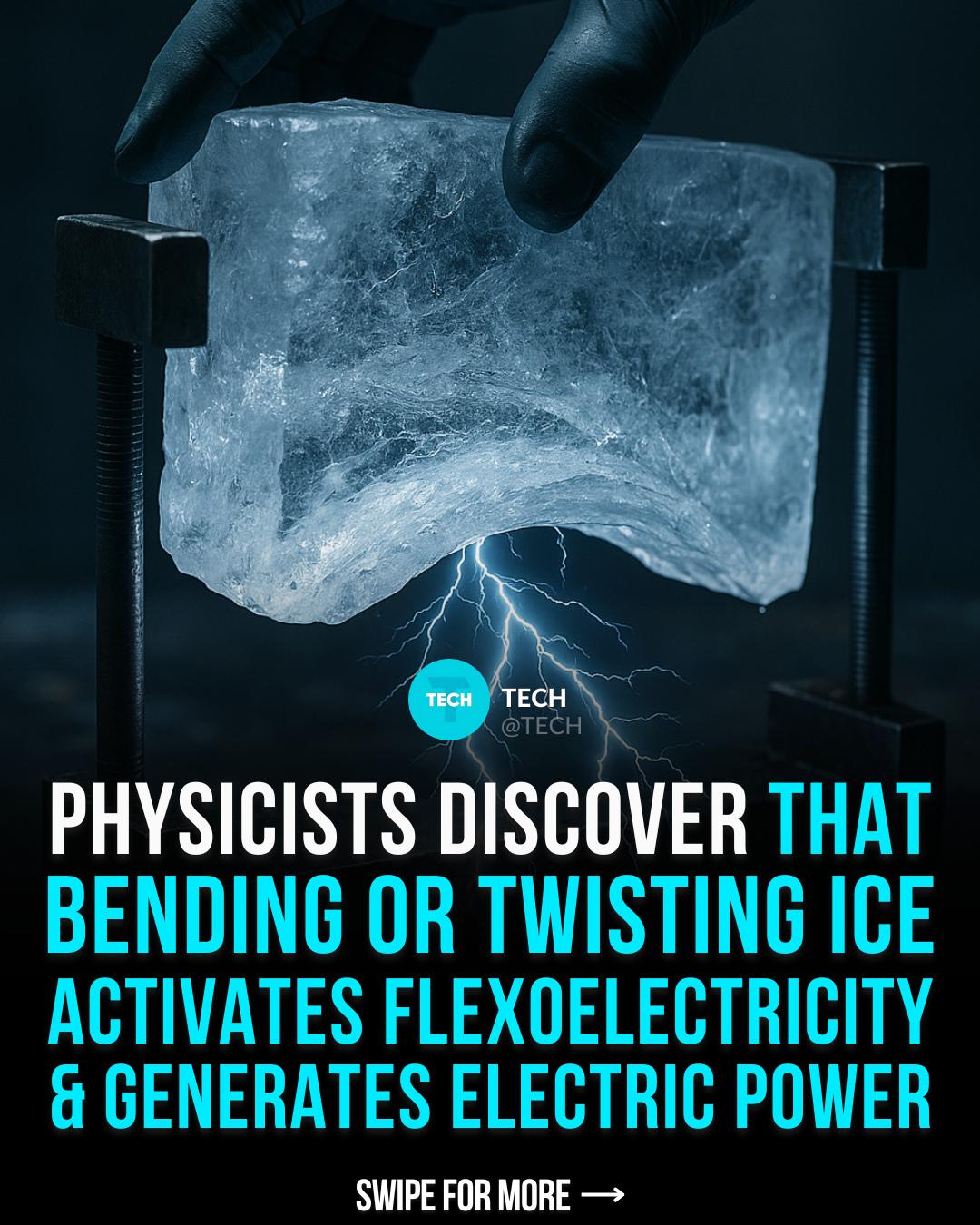

What if the ice in your freezer could power a circuit? A new study in *Nature Physics* reveals that ordinary frozen water, long thought to be inert, actually generates electricity when bent, stretched, or twisted. This effect, called flexoelectricity, turns ice into an unexpectedly active material whose electrical signal rivals engineered electroceramics like titanium dioxide and strontium titanate.

Unlike piezoelectricity, which needs a crystal without inversion symmetry and responds under uniform stress, flexoelectricity can occur in any insulator when the shape curves unevenly. Ice fails the piezoelectric test because its hydrogen atoms are disordered across the lattice, yet when deformed it produces a clear, measurable charge.

In controlled experiments, researchers bent a slab of ice between metal plates and saw voltage rise directly with curvature, holding steady across the entire solid range up to melting. At extreme cold, they found an added twist, a thin ferroelectric surface layer that could flip its polarization under an external field while the bulk remained neutral.

This insight may help explain how thunderstorms charge up. In clouds, jagged collisions between ice crystals and graupel produce fields that spark lightning. Flexoelectricity provides a tangible mechanism for those uneven impacts to generate charge, aligning lab data with atmospheric observations.

The breakthrough also hints at new technology. Cheap, moldable, and abundant, ice could be harnessed for cold-environment sensors or pressure-to-voltage converters. By relying on shape and curvature rather than rare elements, frozen water emerges not just as a backdrop to climate but as a potential building block for electronics.

Source: s41567-025-02995-6

What if the ice in your freezer could power a circuit? A new study in *Nature Physics* reveals that ordinary frozen water, long thought to be inert, actually generates electricity when bent, stretched, or twisted. This effect, called flexoelectricity, turns ice into an unexpectedly active material whose electrical signal rivals engineered electroceramics like titanium dioxide and strontium titanate.

Unlike piezoelectricity, which needs a crystal without inversion symmetry and responds under uniform stress, flexoelectricity can occur in any insulator when the shape curves unevenly. Ice fails the piezoelectric test because its hydrogen atoms are disordered across the lattice, yet when deformed it produces a clear, measurable charge.

In controlled experiments, researchers bent a slab of ice between metal plates and saw voltage rise directly with curvature, holding steady across the entire solid range up to melting. At extreme cold, they found an added twist, a thin ferroelectric surface layer that could flip its polarization under an external field while the bulk remained neutral.

This insight may help explain how thunderstorms charge up. In clouds, jagged collisions between ice crystals and graupel produce fields that spark lightning. Flexoelectricity provides a tangible mechanism for those uneven impacts to generate charge, aligning lab data with atmospheric observations.

The breakthrough also hints at new technology. Cheap, moldable, and abundant, ice could be harnessed for cold-environment sensors or pressure-to-voltage converters. By relying on shape and curvature rather than rare elements, frozen water emerges not just as a backdrop to climate but as a potential building block for electronics.

Source: s41567-025-02995-6